Hang Right Part 4: The Knowledge Quest—Lesson 1

Esther Smith, DPT of Grassroots Physical Therapy, and BD Athlete Sam Elias share how knowledge of human anatomy and body mechanics can help us climb stronger and resolve injury.

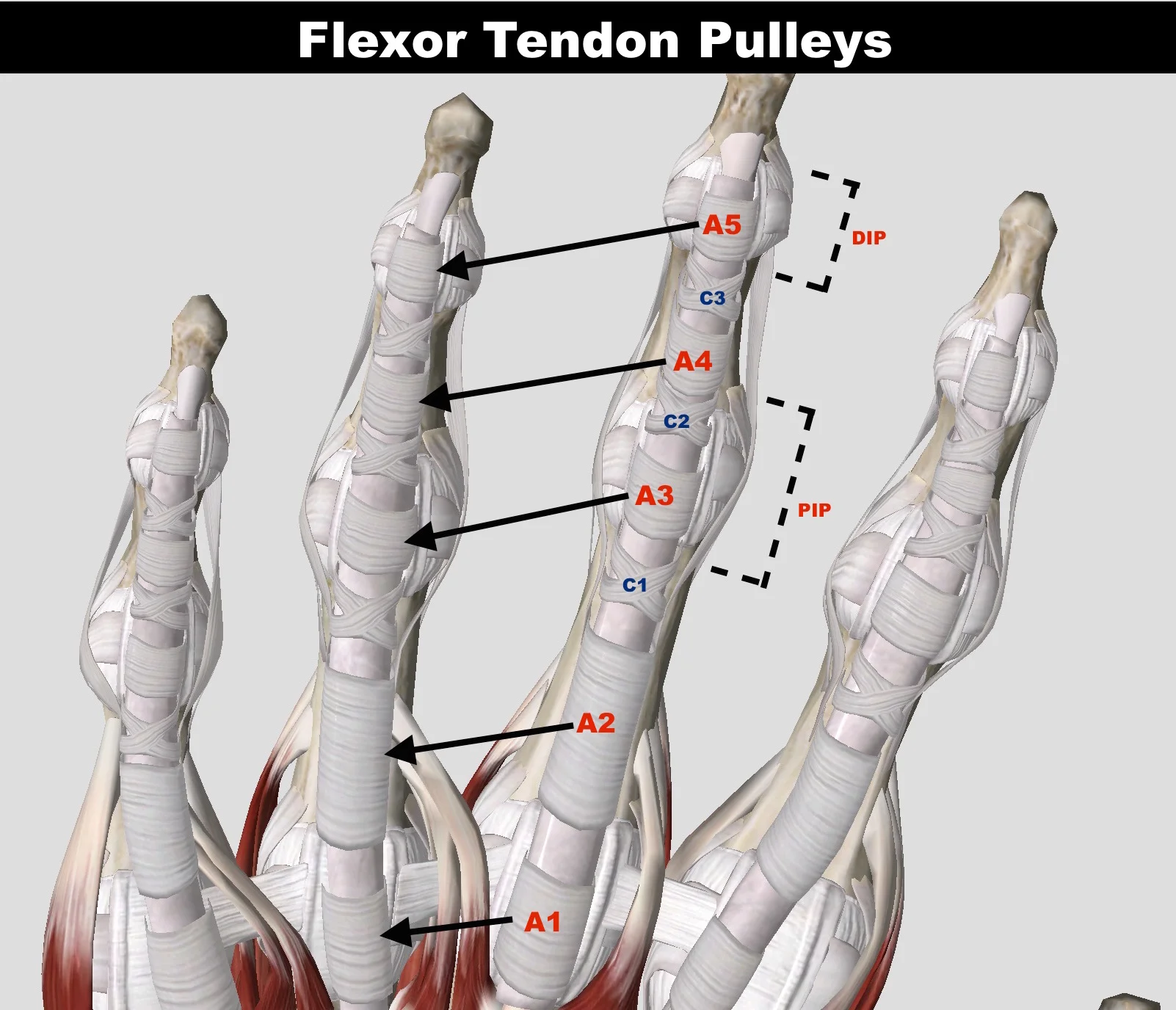

Sam Elias walked into my office with that recognizable look of despair following injury. I anticipated this because I’d received an email a few weeks previously indicating that he “blew his shoulder up” bouldering in Hueco Tanks. He had just redpointed the North American test piece Necessary Evil, 5.14c, and was celebrating his success and fitness by going to Hueco Tanks to boulder. It was his first real outside bouldering trip. His plan after Hueco was to train, and then travel to Spain to get on another long-anticipated sport project. Sam had been training intensively for multiple seasons in order to overcome a redpoint grade plateau. He felt that his training programs had been perfectly suited to his climbing projects and their respective demands. He focused on finger strengthening and increasing his power endurance, while balancing this with consistent physical therapy, including routine shoulder stabilization and antagonist muscle training.

Photos: Katy Dannenberg and Andy Earl Illustrations: Eli Kauffman

How could this injury occur when he felt so strong and at the peak of his performance?

Sam: “I was at the peak of my performance, but in a specialized sense. We can’t train everything at once, and thus can’t be trained for all of the different climbing styles or moves in the same moment. Our bodies are never perfect, and there are always imbalances either from overdevelopment/specialization or old injury/trauma. I’ve never carried a lot of mass in my upper body, and I’m primarily a route climber. I rely on a combination of good technique, as well as good finger strength and endurance to do my best achievements. I also have a +4.5 inch ape index. Additionally, I had a bad subluxation of my shoulder in 2008, and several “micro” subluxations in all the years since. In my training, I’ve heavily prioritized hang boarding/finger strength for about 3 years. I lifted a lot as well, but I wasn’t considering the extremes of the mobility range, which is both where injury tends to happen, but also where “world class” strong differentiates itself from “pretty strong.” My fingers were really strong and I was climbing really well. However, I was completely unprepared for steep, wide climbing, and my shoulder was the weakest link.”

He sat despondent in my office and reported that he had already seen a well known orthopedic surgeon, who reviewed his MRI. He was told that his shoulder was a “ticking time bomb”. He was informed he needed immediate surgical repair on a chronic labral tear and acute, partial subscapularis tendon tear if he was to continue with his professional athletic career. Sam was shocked by this news because he actually didn’t feel much pain, and he was able to perform, climbing relatively well despite feeling weak in his shoulder.

Sam: “I was angry, and filled with a lot of doubt and dread. But, I’m really in tune with my body. With each passing day, I listened to my body, and also to the advice of many people. I didn’t know what to do. I just went day by day. I learned as much as I could. Then, the decision became obvious, and basically made itself.”

Sam’s MRI was telling: showing an image of a degraded, inflamed, partially torn and frayed shoulder joint. However, this image wasn’t concordant with his reported symptoms. Some of the tissue damage was acute, but most of it was long-standing. A thorough mechanical physical exam and second surgical opinion would be necessary. After I subsequently evaluated Sam’s shoulder, we both agreed that his level of pain and weakness was manageable. With a therapeutic, multidisciplinary approach, he was able to explore other options than to go under the knife immediately. If we strengthened and reconditioned his damaged muscles and addressed the likely root causes of this failure of tissue, perhaps Sam could come out stronger, more informed, better organized, and avoid the trauma, cost and recovery time of shoulder surgery.

Sam built a team of providers, all experts in their field, and set out on a quest to understand the missing links in his physical training, and the holes in his knowledge of anatomy and functional movement.

Sam’s correspondence to me a few days later:

“In all my training, I've done shoulder antagonistic/opposition work as secondary or even tertiary. I was always planning to make it the primary focus for these 6 weeks of training even before the incident a week ago. I really think I can get my shoulders A LOT stronger. Then, maybe I wouldn't need surgery ever. If my labrum has been torn since 2009, when I originally subluxed it, then I've done literally everything in my climbing life with it, and it's only given me problems at very specific and understandable times. Coupling that with the fact that I can gain a lot of upper body strength and muscle makes me feel like I should try that first. I'll get crazy with it. Be super diligent. Do whatever it takes -- however many days of the week, and hours of the day -- training, stretching, stability, PT, massage, acupuncture. After all, I can always get surgery.”

As a PT who commonly treats athletes, it was rewarding to watch Sam’s knowledge quest take off. His commitment to the process, and acknowledgement of the time it takes to recover yielded results accessible to anyone willing to put in the time and effort.

Sam offers the following tips for navigating injury: - take ownership and responsibility for the injury and your body - get hungry for knowledge and understanding, obsess over the details, talk to as many people as possible - form your own belief and opinion, so that you know what you’re doing is right - don’t just blindly put your body into someone else’s hands

Disclaimer from Sam: “Every body is different, and has a different history. Every injury is different. At the end of the day, each person must evaluate their situation and decide for themselves. There is no magic pill. No magic person. No magic surgery. The magic lies in the individuals’ belief in their knowledge base, and their decisions.”

The following Missing Links are what led Sam to his own salvation and confidence that he could be strong again and avoid injury in the future. This is a story about Sam’s recovery, diligence, and ability to avoid surgery, outlined in four lessons. These lessons are common missing links in a climber’s understanding of their anatomy, climbing movement, and strengths.

SAM’S MISSING LINKS

KNOWLEDGE QUEST LESSON 1: HOW THE #*@! ARE OUR ARMS ATTACHED TO US ANYWAY?

Your new climbing BFFs’...The Serratus Anterior and the Latissimus Dorsi and the engineering of proper push-ups and pull-ups

The serratus anterior muscle and the latissimus dorsi (Lat) are two of the most overlooked and misunderstood muscles of our arm-to-torso muscular attachment complex. These two muscles, along with a few others, make up the “sling” that holds our shoulder complex to our trunk. They become integrated, as part of our “core.” As climbers we need to pay extra attention to this anatomy as it is the link between our fingers, arms, and the rest of our body. In the diagrams below, you can see the span of these two influential muscles.

The latissimus dorsi muscle originates along the back of the crest of our hips and spans up to the mid-back, attaching to our shoulder at the inner, upper arm.

The serratus anterior muscle lays over the rib-cage beneath the latissimus, hugging the bones of ribs 1 through 9 and spans beneath the scapula (aka the shoulder blade) to attach on the medial border, closest to the spine. The serratus integrates with our oblique muscles in a knife like pattern at the side body, thereby seamlessly integrating our shoulders into our abdominal wall.

Let’s take an in-depth look at the serratus anterior, one of the key muscles that attaches our arms to our trunk. This muscle provides us with three very important functions:

1) “Punch” action of the scapula, sometimes called the “boxer’s muscle”

2) Sling effect that draws our rib cage into our scapula, in other words the muscle that prevents our shoulder blades from lifting off the trunk (the anti-winging muscle)

3) Upward rotation of the scapula

Primary function 1: Inactive Serratus

Primary function 1: Active Serratus

Active Serratus and correct position for plank or start of a push up.

Primary function 2: Sling effect illustrated in a plank or at the start of a push-up. An active serratus slings or harnesses the rib cage into our shoulder blades. This action prevents drop of the trunk towards the floor and allows the scapula to be wide and flush on the back.

This knowledge can help inform a proper push-up, which can become a true antagonist exercise that focuses on the push aspect of movement, and a serratus training exercise, if performed correctly. Scapular "winging" is a result of a weak serratus among others (e.g., rhomboids) and is a common movement error. Many climbers make this error while climbing, especially in wide, shoulder-heavy moves, and while doing push-ups. Attention to this movement during push-ups can lead to proper movement when under more significant stress and a weighted load while climbing or lifting.

Note the sling effect of an active serratus that allows the shoulder blades to be kept wide and flush against the ribcage. Shoulder blades naturally draw together at the bottom of a push-up and return wide and flat across the back at the top.

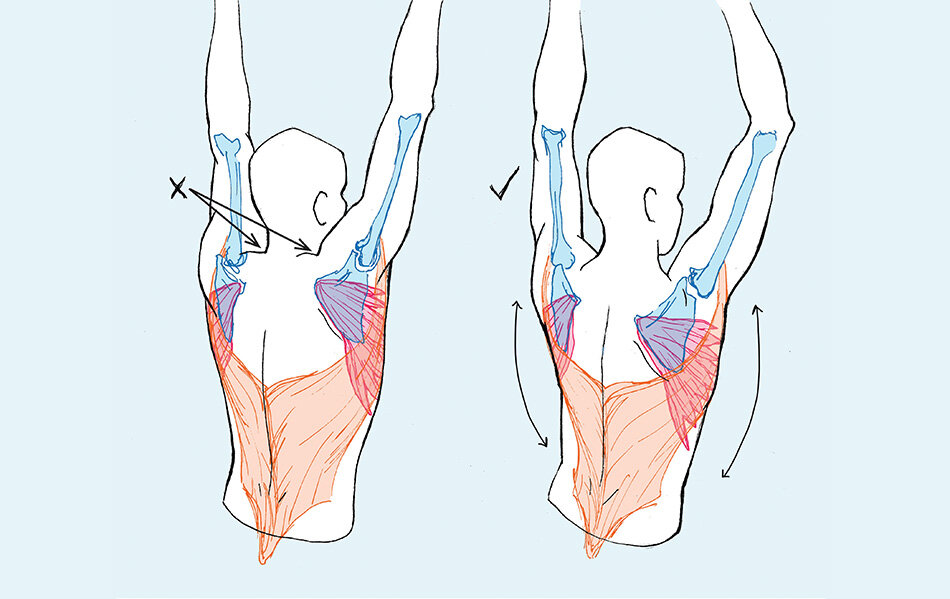

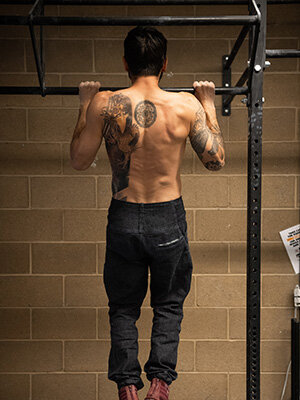

So far we have examined our shoulder complex in push motions when our arms are in front of us. But what happens when our arms go overhead? The third function of the serratus anterior muscle supports us in the more vulnerable and demanding overhead activities of climbing and hanging. Note in the illustration below, the serratus anterior action of upward rotation of the scapula. When the scapula upwardly rotates it supports our arm in overhead movements, helping to secure our shoulder complex on our trunk and to position the ball and socket joint of the shoulder in the most optimal way. The serratus joins forces with the latissimus dorsi to assist us in a proper hang and pull-up.

Primary function 3: Upward rotation of the scapula

Welcome to your primary “pull” and “hang” muscle. The latissimus dorsi (The “Lat”) does more to pull than the bicep, and it is an underutilized, powerful, broad muscle that is designed for pulling, hanging, and climbing movement. Underutilization of the latissimus dorsi is a main reason why people have trouble with proper pull-ups and can contribute to wear-and-tear injuries at the shoulder. Let’s take a closer look at the Lat. This muscle provides us with two very important functions (among others):

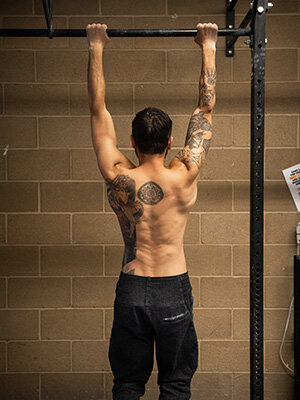

Hang: static engagement and lift of the trunk within the frame of the arms

Pull-up: the latissimus continues its upward lift of the trunk, drawing the humerus (the upper arm bone) down towards the side body (this action is referred to as shoulder extension)

Hang: In a proper hang the Lat encourages a static engagement and lift of the trunk within the frame of the arms as shown on the Right. If the lat were to turn off, the trunk would slip through the arm frame like a bag of rocks, shown on the Left.

Pull-up: As we go from a hang to a pull, the Lat provides a connection between the waist and the humerus (the upper arm bone). While executing the pull, the Lat continues its upward lift of the trunk, actioning the humerus into extension, thereby drawing the upper arm bone towards the side body. This sequence illustrates initial recruitment of the lat to pull the bulk of the weight up, followed by secondary recruitment of the smaller elbow flexing muscles (biceps and friends) to complete the elbow lock off position.

Every climber must know how to do a proper pull-up. Antagonist exercises have their place, but a proper pull-up uses many of our primary climbing muscles. Our anatomy is evolutionarily specialized for climbing and the Lat plays as key of a role in this as our opposable thumbs. Attention to Lat engagement and use of the Lat as the primary pull muscle during pull-ups will lead to healthier movement when climbing.

Join us for our next installment of Hang Right Part 4: The Knowledge Quest—Lessons 2-4 as Sam continues to explore his human anatomy and body mechanics to help resolve his shoulder injury and climb harder and smarter.